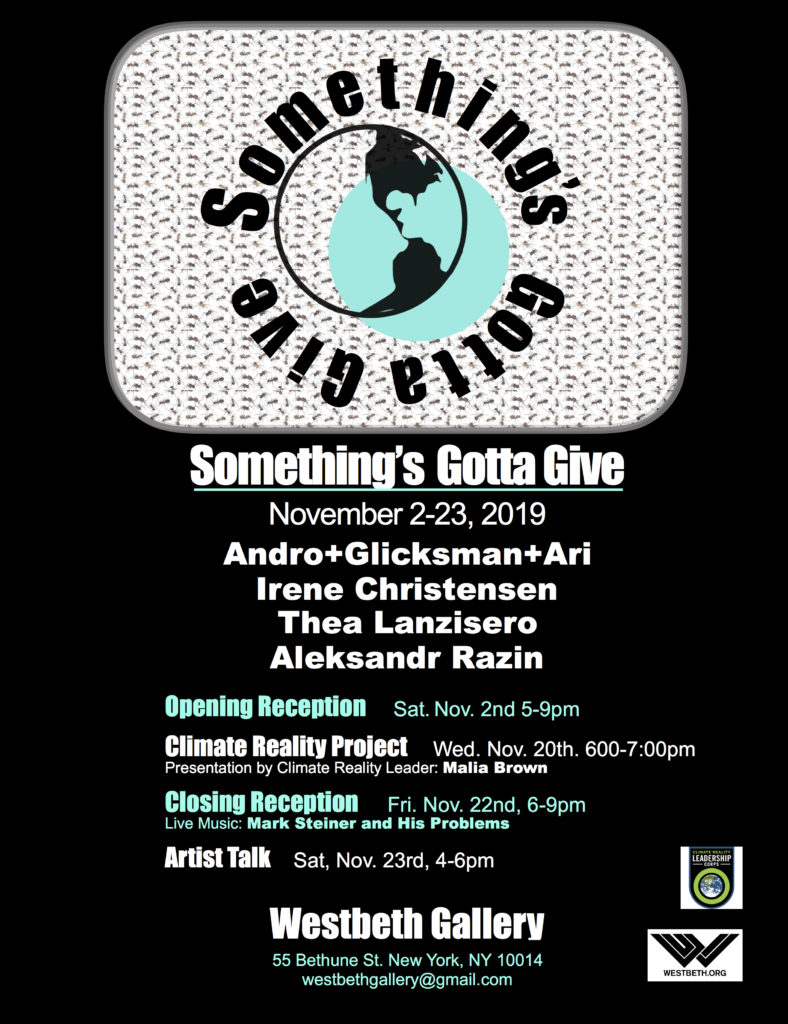

Something’s Gotta Give.

In an exhibition that confronts the current state of the country, humanity and the planet, six artists deliver four perspectives that challenge us to experience the human condition as they see it. Ginger Andro, Chuck Glicksman, Mark Ari, Irene Christensen, Thea Lanzisero, and Aleksandr Razin join their voices—in sculpture, installation, and paint—to those rising all over the world to demand a major change in attitude and action. Our survival depends on it. Something’s gotta give.

Westbeth Gallery

55 Bethune St. New York, N.Y. 10014 westbethgallery@gmail.com www.WestBeth.org

November 2-23, 2019

Opening Reception Sat. Nov. 2nd, 5-9pm

Wed.-Sun. 1-6pm